If there’s a hell, they’re all going.

- Charlie Bonner

- Jul 20, 2018

- 13 min read

Los Angeles — Las Vegas —The Grand Canyon—Sante Fe—El Paso

“It gets worse every day,” Jeannie says on the state of politics as we chat over lunch in Los Angeles, “I’m very disturbed by it.” I have taken a break from my double-decker bus tour of Hollywood to grab something to eat when I meet Jeannie, and we start, as I always do, talking politics. “I vote for a normal human being,” she tells me, rather than associating with a specific party, “but I know how people have their agendas.” To Jeannie, corporate interests too often tangle with these agendas and corrupt the political system, “but you can’t buy love and friendship,” she says, taking a sip of her lunchtime white wine. She is currently being treated for her second round of stage four cancer, so the politics of the healthcare system are a focal point for Jeannie. Because of strict FDA regulations, Jeannie drives to Mexico to receive specialized treatments that once before saved her life. This part of Jeannie’s story is especially heartbreaking. Our healthcare system is so broken and rigid that she has to travel to another country to seek lifesaving care. And yet, we so often treat debates around health care reform with a distance that dehumanizes those, like Jeannie, actually receiving treatment. Are our politics really this inept? Over the years, she has watched the situation on the border evolve into catastrophe driving back and forth, “it’s terrible to watch what’s happening on the border.” Harsh policies and political inaction have created an immigration situation that is reaching its critical mass. By Jeannie’s estimation, even this situation comes back to big money’s political influence. “People are making money off all that,” she says of the children’s detention centers, noting that we have a system where the investors for detention centers and prisons donate to campaigns and then seek a quid pro quo relationship. “If there’s a hell, they’re all going.” She often comes back to this issue of corporate influence during our lunch, “the politicians are pretty much purchased right now,” she says. Whether it be the city council and developers or US senators and big pharma. “The pharmaceutical companies run the show here; I have a big problem with that.” To seek the care she needed in Mexico, Jeannie had to sue her government based insurer, “did you know, the government has to let you sue them?” she asks me. She has a pile of records, receipts, and legal fees to prove it and now that she has been diagnosed again, she will have to start the process all over again. “I’m waiting till it cools down in my apartment to go through the piles again,” the record-breaking heatwave has put a pin in her plans. The government, “wants to take away our rights to do what’s natural,” she says, “you know what, screw em.” I wish I too had a lunchtime wine with which to cheers her. “It is my body, and I should be able to do what I want.” She segues this notion into the news of Justice Kennedy’s retirement and the possibility of rollbacks to abortion access, “This whole Roe V. Wade thing, I mean I’m not having kids anymore, but I’m out of my mind about this,” she says with frustration, “It’ll go back to the days of using the coat hanger, she says, shaking her head in disgust. All of this, while “these politicians are out there screwing everyone and no doubt getting them pregnant and then spending our money to fix it.” But she doesn’t want us to get too wrapped up in controversies such as these; they’re “causing so much division.” But this isn’t by accident, “it’s on purpose, it’s a smokescreen. We’re not even looking at the needs of the community,” she adds. Having worked herself up at this point, Jeannie takes another drink and concludes, “What’s gonna happen? Seriously, what’s gonna happen?” I hop back on the double-decker bus, and Jeannie’s question sits with me as I ride through the palm trees and movie studios, what is gonna happen? It certainly doesn’t seem like it’s going to get better anytime soon. I cannot count the number of school shootings, indictments, scandals and tweets that have occurred since I started driving. I revel in the hours of solitude in the Jeep keeping me from checking the news. Seriously, what’s gonna happen?

My next stop is sure to have answers—Las Vegas is known for its moral clarity. Respecting the most lawful compact of Sin City, I don’t interview anyone to preserve what happening in Vegas staying in Vegas. But I can’t help but think about the state of politics as I walk down the strip, I am mesmerized by how artificial it all is. I am captivated by how much people crave the imitation. Why go to Rome when you could go to Cesar’s palace? Why travel to Venice when you can ride a gondola through a hotel in the Nevada desert? The amount of money people spend on blackjack could easily finance a trip to Paris, but the Eiffel Tower on the strip seems to be enough. When you think about it, of course, the lines between truth and fiction have been blurred; we’ve been asking for that for years. Why have a politician for a president when you could have the reality TV version of a president instead? We have a man who for a decade appeared in our living rooms, sitting in high-backed leather chairs, decisively an executive. Trump was synonymous with business and a specific, albeit false, depiction of the American dream. For a citizenry far removed from the day to day function of politics, this depiction of a leader is close enough to the real thing to count. He is the neon-lit, fake gold plated, larger than life, porn-star fucking, vision of success that this town has fed to the world for generations. He is our Las Vegas President. Hell, his name is on the gilded skyscraper that hovers over the street. Why are we surprised? Frustrated and grasping for something real, I head east for the Grand Canyon. Words cannot do this place justice. Its vastness brings you to awe-inspired silence. It is phenomenal. For all the things that politics seems to ruin in this country, protecting spaces such as this is one of our great victories. As writer Wallace Stegner wrote, “National Parks are the best idea we ever had. Absolutely American, absolutely democratic, they reflect us at our best rather than our worst.” I couldn’t agree more.

So too does art reflect this commitment, and there is no better place to engage with art than Sante Fe and nothing in Sante Fe speaks to this more than Meow Wolf. Unique and immersive art installations fill what was once an old bowling alley. Making my way through its neon-lit caverns, its refrigerator turned portal, its gallery of weird, I meet a psychic in an air stream. I am not entirely sure if she is part of the installation or is just a patron who has taken up shop in one of the museum’s crevasses, regardless I sit down. I know what you’re thinking, Charlie, you don’t seem like one for tarot cards. Well, dear reader, these are desperate times, and we have to take all the help we can get. She reads my tarot cards as we talk politics. “This isn’t a democracy, this is an oligarchy,” she tells me. She sees our military industrial complex as one of the largest issues perpetuating strife in the country, “even Obama took two wars and made it seven,” she adds. She has seen first-hand how politics can drive people apart, “When Obama was elected, I didn’t talk to my brother for five years,” noting that his conservatism drove a wedge in their relationship. Five years is a long ass time, I think to myself. She flips my cards and hovers her hands over each one, “interesting, oh very interesting,” she says with surprise. They tell a story of using communication to break through and connect with people, of how writing helps communicate the connection to others, of success. A little on the nose, if you ask me. “Oh, I wanna know how this works out,” she says, handing me her card, “keep in touch.”

“I try to see both sides of the coin,” Robin tells me as we sip our coffee at Sante Fe’s Iconik Coffee Roasters. Robin is a California transplant who has stood out in both communities as a vocal Christian conservative in traditionally liberal environments. “I’m conservative, but on many issues, I’m very moderate,” she notes. We talk at length about the frenzy that has ensued as a result of the politics to which she responds, “I don’t have this panic mode thing—I believe in Christ.” She leans back in her chair, points up to the skies and smiles. “If Armageddon happens tomorrow, I don’t worry. I know where I’m going,” she says with a wink. If I'm honest, part of me is jealous of Robin. She is genuinely, the calmest person I have spoken with this entire trip. Her belief that a larger power will guide things regardless, her “I pray for wisdom for whoever is in office,” vibe, really seems to be bringing calm to her life. There is a level of removal from the harshness of the Trump policies given her socioeconomic status that I think has to help as well, but still. I miss being calm. What a privilege. As she sees it, many on the left are just protesting for the heck of it, “Hating someone for the sake of hating someone is nuts,” she says. “They’re so young. They haven’t lived enough. They don’t know the history.” She wants to tell them, “There is a way to disagree peacefully.” On Trump Robin says, “Have I loved his personality? No! But that’s okay!” She explains, “He doesn’t have to be my best friend.” Robin is less concerned with the scandals of personality than she is results, “if he’s getting stuff done, making headway, is that such a bad thing?” Yes, Robin, it is such a bad thing. Sigh. She agrees that immigration is fundamental to the American identity, that it is “like second nature” to the nation, but qualifies, “somehow, somewhere, there has to be some control.” It is an America first notion that she thinks we need, “focus on the people here and taking care of them.” Robin is deeply concerned with making sure people here are getting taken care of, she worries about those without health insurance but saw Obamacare as a failed solution. “How can you fine people who can’t afford it? That’s very squirrely and wrong,” she says definitively. It is a very complicated situation she concedes, “all these different situations, that’s why I lay in the middle.” I must concede, she hasn’t said anything that I would classify as the middle, but she has reiterated that point multiple times. “It doesn’t matter who’s in office, there’s always going to be something,” Robin laughs. Robin has noticed the evolution of negative discourse, but she doesn’t let it bother her. “I don’t get in heated debates,” she says, “People here are very opinionated, but they’re very respectful. They’re very accepting, so you’re not afraid to share your opinion.” Robin knows she is normally in the minority politically, but she speaks up when it is important. She finds common ground with those she disagrees with by focusing on local issues, like low-income housing. Robin uses her background as an interior designer and architect to help local non-profits attempting to make up for Sante Fe’s rising cost of living that is pricing many out of their community. She always tries to ask herself, “how do I help locally?” and then she gets to work.

Across town, I meet with Tom, who’s politics are similarly guided by his faith, but to a different result. “Our curses and our blessings are attached at the hip,” Tom tells me, referencing the landscape of leftist politics in New Mexico. Tom is a full-time activist in Sante Fe, coordinating hundreds of grassroots volunteers to knock on doors to elect Democrats, while his wife runs the phone banks. “We have to run up the Democratic numbers in Sante Fe to counteract the rest of the state.” Before now, Tom ran the United Methodist Committee on Relief, preceded by his stint as a Methodist minister. “I come to my politics by my ethics,” he notes. I ask him what he thinks about the state of politics today, “I can imagine politics being healthy and me not liking it,” he responds. “Politics is a discipline,” a process that brings values to fruition, “the content is ethics.” Tom is driven by the values but is also deeply concerned with those who can get things done. “I’m not voting for people based on what they stand for. I’m voting for people based on what they’ve accomplished. I will never go to the mats on what someone stands for. They’re not statues, that’s all statues do, they stand for things.” By his estimation, too much of the progressive movement is wrapped up in what people stand for, with little care for history or practicality. “Don’t tell me you’re a progressive and don’t know who Terry Roosevelt or FDR are,” he quips, “shouldn’t American history be a prerequisite to being a part of this movement?” He is the son of Holocaust survivors who paid off bribes at Elise Island to gain entry to the country, “When people want to know about illegal immigrants, I raise my hand,” he jokes. We have forgotten what it means to be an immigrant, what situations drive a person to our shores. People like Tom’s parents, like central American asylum seekers, like those who no longer can even make the trip because of the Muslim ban. We have forgotten what it means to be an immigrant. So too does Tom comes from a family of Republicans, so he learned early on how to navigate the difficult waters of political discourse. “American political conversation has become if you don’t agree with me, I’m offended,” he notes, eroding those values he learned as a kid. “This country’s capacity for discourse went straight to hell.” But, he notes, we have to have some historical perspective to this problem. Living through Vietnam and Watergate, he has seen worst discourse; he has seen times from which people thought politics could never recover. “People say discourse has gotten worst? They haven’t seen worst. It may be worst than last week, but that doesn’t mean ever. Ever has some pretty grand dimensions.” That said, Tom’s focus is not on engaging Republicans and bringing them to the left, his work is centered on the internal politics of the Democratic party. To the Republicans, he says, “I’m trying to prove you irrelevant, I’m not trying to make you better.” He wants to recruit and run Democrats who can win, politicians of substance that are pragmatic enough to get things done. “The Politicians I don’t respect,” he adds, “are the ones that run from their past.” In this interconnected age, it’s almost impossible to run from your past, and yet people still try. “Your past is yours,” he warns them. A lot of these values and lessons learned were forged in the fire as the minister over the Castro district in the height of the AIDS crisis. He tells me stories of buying up properties and lending them to crisis groups, of starting the quilt project in his office, of fighting stigma, of hiring a UT architecture professor to design spaces for patients to die in comfort and dignity. “I realized not just that politics mattered, but that stepping into the fire mattered,” Tom says. So many in churches and state houses were willing to look away from those in agony when the time called for action. “We were serving tens of thousands of AIDS patients, and what was I? A hippie dippy Methodist minister,” he pauses in remembrance, “I buried countless people younger than me.” My mind wanders; only a week ago I was walking those same streets. They are jovial now, gilded in rainbows. The church is gone now, the building Bank of America gave him to house patients is now a soul cycle. Times change fast. Even the church has changed, their once steadfast support of liberal causes has shifted and evolved, so Tom left. As the times have changed, these pillars of community have changed. From churches to political parties to the government itself. But, Tom hasn’t changed. “Institutions have drifted in their identities; we have not.”

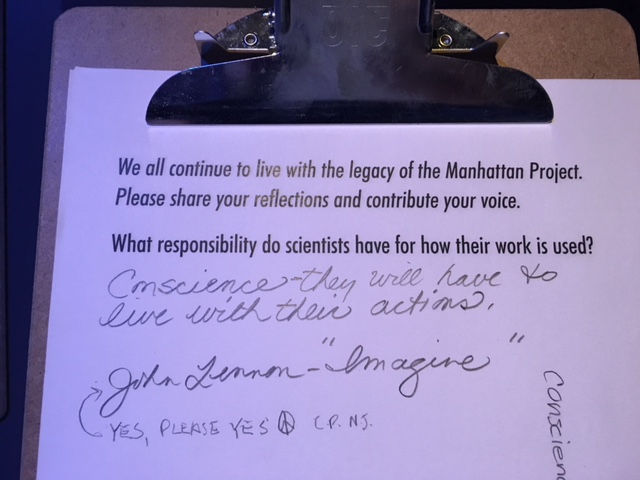

After our conversation, I drive out of town aways to Los Alamos, the nuclear city. Here, the world forever changed. it is a city completely defined by its relationship to nuclear weapons, at a time when the risk of nuclear war has become more prevalent, I wonder how that singular definition feels. Much in San Francisco, there is space at the local museum for reflection.

With that, I head south.

“For me, it’s easy to take the border for granted,” Robert tells me as we sit on one of the antique couches at the El Paso Historical Society where he works. “El Paso as a border community is very isolated.” Though many pass back and forth with ease in El Paso, some see it as the end of the line, the wrong side of the tracks, “The border creates a geographic and mental border for people,” noting he hasn’t walked over in nearly ten years. It is a fixture of the community, economically and personally, “if you don’t have family crossing back and forth, you know someone who is,” Robert says. That said, “immigration doesn’t come up that much in local politics,” it’s just a given. While other cities like Austin and Dallas debated their role as sanctuary cities, El Paso debated the preservation of historic neighborhoods. But all of the political disagreements in this border town are watered down by the fact that, “voter turnout in El Paso is generally very low.” People are noting showing up and holding politicians accountable, as a result, a small number of people run local politics and corruption is not unusual. “There is an active political community, but it’s the same people,” Robert has seen this unfold first hand, getting involved in the Obama reelection campaign. “It’s very tribal, the same people running the show.” Arguably, the whole system is tribal; he remembers the anger that he and other volunteers would often receive. “There’s so much hate, it gets you on a visceral level,” recalling one instance in which a friend was told, “I hope you are driving down the street and get hit head-on by a semi-truck.” I wonder if he’s been to the California state capital. The biggest local issue right now surrounds the placement of a new downtown arena to attract larger acts to the farthest point of West Texas. Voters approved it in a 2012 quality of life ballot initiative, but the location was never part of the ballot verbiage. Outrage ensues. “The debate has brought out the worst in the city,” he notes, pitting historical preservationist, neighbors, and community leaders against one another. This too, comes back to low voter turnout, “That precinct doesn’t vote,” it is a heavily Mexican-American, middle-class neighborhood, where voter mobilization is difficult. Because they don’t vote, “it was an easy decision for the city to say they can just move these people.” And yet, voter turnout remains low. Nothing has changed.

That evening, I gather a group of friends and walk across that same border Robert hasn’t crossed in a decade. On the way there, we hang fifty cents to a latex-gloved woman and meander across the bridge that separates our two nations. That was it, no one even asked for an ID or passport, only a mere fifty cents. I have now, in one swoop, been border to border and coast to coast. The El Pasoans serving as my makeshift tour guides know how to navigate Juarez, one of the most dangerous cities in Mexico. They whisper over margaritas at the Kentucky Club, where they were invented, I stare, “oh, we will tell you when we cross back.” I feel a lump in my throat. We have our drinks, eat an incredible dinner and make the trek back into the city. Security on this side is much more serious, but it only cost twenty-five cents. “You get a discount if you make it back,” one of the girls jokes. We make it through customs with just my driver’s license. Now back on home soil, one of the girls says, “Someone was murdered there last week, but it was about the elections, we don’t go over there around elections.” I think back to the Tom in Sante Fe, “People say discourse has gotten worst? They haven’t seen worst."

Comments