Fuck This Bunting

- Charlie Bonner

- Jul 12, 2018

- 11 min read

California (Sacramento-Napa-San Francisco-Los Angeles)

Maybe politics has always been toxic; perhaps we are just starting to pay attention. It’s a thought that crosses my mind the California state capital as the tour guide shows me a picture of a semi-truck crashing into the building. “Blaring its air horn and accelerating at high speed, a big rig smashed into the south side of the state Capitol last night and exploded in a fireball as the Assembly ended a meeting on California's energy crisis,” reads one article from the incident in 2001. “He was very unhappy, made some—not threats, I don’t want to indicate that—but voiced discontent with the California government, as well the governor of the state of California.” I think about this visceral reaction again looking at the portrait of Governor Ronald Regan. It now sits behind a plate of glass, unlike the neighboring portraits, because it was previously slashed with a knife. Politics is toxic. The tour includes all sort of throwaway stories like this, just a little color to the tour I suppose. He tells these stories alongside the architectural history and odd parliamentary procedures, “the Governor can’t walk into the Senate or the House Chamber, or he can be arrested,” he notes, “it has only happened once.” Governor Jerry Brown, who somehow has been governor on and off since the mid 70’s, walked into the Senate in outrage—he was promptly arrested.

Aggression and indignation seem a part of the political foundation of California, take the flag, for example, still bearing the word ‘republic’ with a menacing bear at its center. It is a reminder that California is ready to protect its sovereignty, from its inception it has been prepared to break off, to become its own republic. That said, it shouldn’t be surprising that talk of succession and breaking up have become almost commonplace in California. In a government where each state senator represents more than one million people and the budget totals $200 billion, these discussions have serious consequences. It is one of the funny things about tours such as this, the weighty facts are well-rehearsed and thrown out with ease, each one something to marvel at as much as the gilding on the domed ceiling. Tourists consume them with nothing more than a nod while I take notes in my legal pad with vigor.

This is on my mind as my brother joins me and we drive through the valley outside of Sacramento towards the Napa Valley. I am determined to spend the Fourth of July holiday in a small American town, something in my mind equates the smallness of a locality with its inherent level of patriotism. I want red, white and blue bunting. I want little league baseball teams. I want kids in wagons waving pint-sized flags. Curiously, Napa is that sort of small town, just with really outstanding wine. With our patriotically themed garb on, we gather with the locals on the sidewalks of downtown Napa in anticipation of the parade. It is what I think of when I think about the holiday; it checks all those boxes in my arbitrary list of patriotisms. Save for a few Mexican-American dancers, it is also very white. Almost grossly white. Why is it that the images I associate with celebrating American-ness manifest themselves so starkly in whiteness? I suppose there are many obvious reasons for this, but the notion sadness me. It makes me angry that I yearned for these things so dearly without a second thought. My Rockwellian idea of finding America in a small town doesn’t equate with the values of diversity and equity we spout. On second thought, fuck this bunting. Fuck this whitewashed version of America. Do we really feel the same way as Sarah Palin who once noted, "We believe that the best of America is in these small towns that we get to visit, and in these wonderful little pockets of what I call the real America, being here with all of you hard working very patriotic, um, very, um, pro-America areas of this great nation. This is where we find the kindness and the goodness and the courage of everyday Americans." That's not who we are, or maybe I should say, that's not who we should be. People that split America up into real and fake parts, that divide a nation among lines painted across old fashioned Time magazine covers. I feel profound shame in these thoughts. When your mood turns like this, as is often the case in this political climate, patriotism can feel a lot more like nationalism. The small children with their pint-sized flags seem more chauvinistic than prideful. Can we celebrate striving towards our shared values and still be ashamed of the country as it stands today? I guess that’s a lot of nuance to spell out on a parade float.

The float for the Napa Valley Culture of Life drives by proclaiming they are “defending life from conception to natural death.” A painting of a fetus appears dressed as Captain America, “heroes come in all sizes.” This, I believe, is our cue to leave. Thank god for the wine.

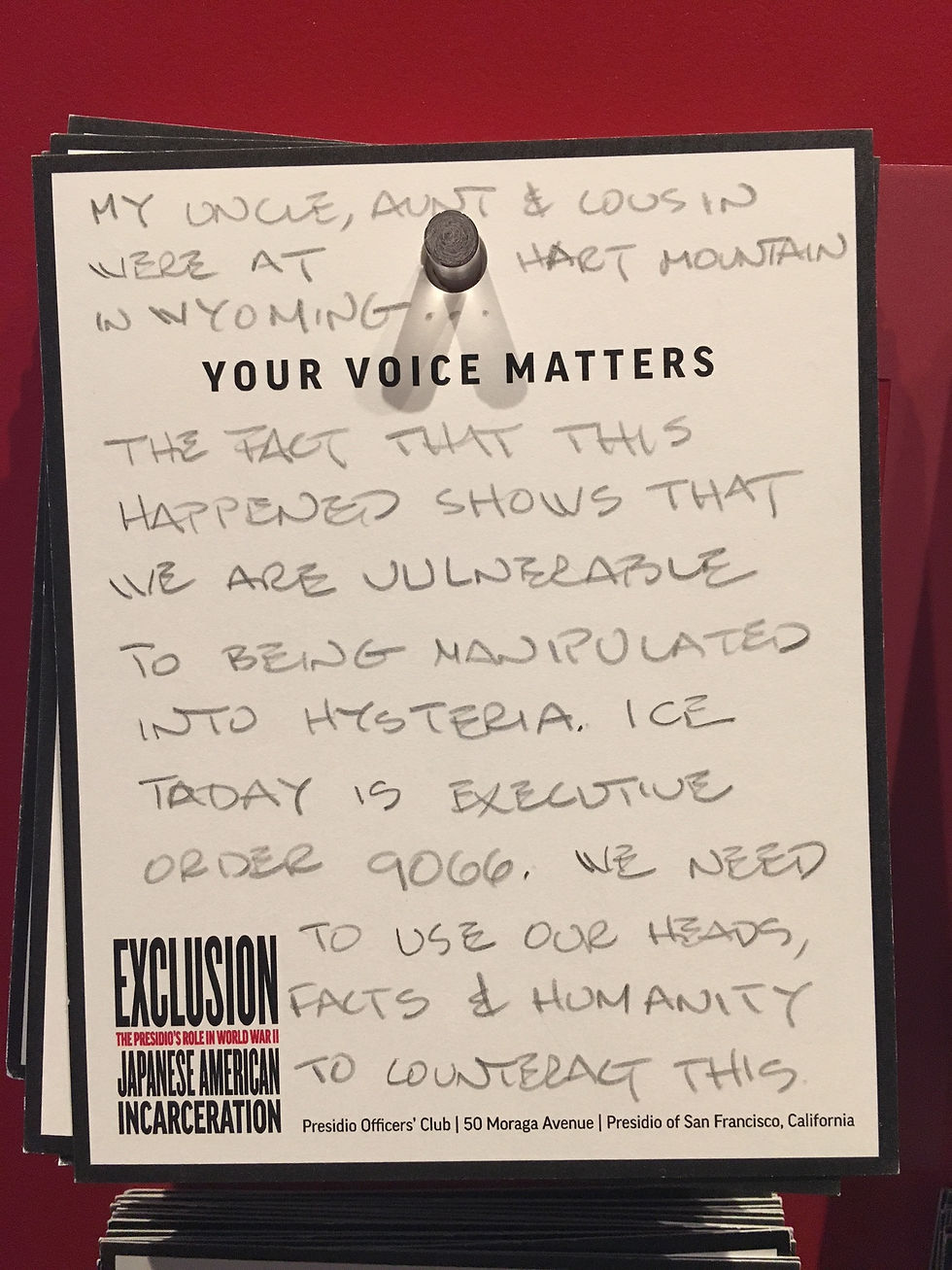

We spend the next several days in San Francisco where we visit the Presidio, a gorgeous area on the bay that overlooks the Golden Gate Bridge. It used to the home to both Spanish and American military bases, but today it is a collection of museums and protected wildlife spaces. One of the exhibits is a retrospective on the Presidio's role in Japanese internment, it is a powerful exhibit that has been extended by more than a year because of its popularity and relevance to today's politics. Ironically, the most moving portion of the exhibit for me is not the artifacts or analysis--is is the reflections from other visitors. I still on the floor in front of a wall where note cards are hung up with the thoughts of those who have walked this museum prior. I get lost in their simple observations, in the profoundness of their thoughts and worries.

“I feel more guilt than gratitude,” Asha tells me at a Café in San Francisco. The popular concept of gratitude towards being born American doesn’t resonate with her. In being thankful for being born in America, you are inherently saying, ‘thank god I wasn’t born over there,’ where ever over there may be. It is an American centric view of the world that doesn’t sit well with Asha, nor a whole generation of young progressives, she believes. She is from the upper east side of New York, a place in which people are traditionally socially liberal, and very fiscally conservative—but that is shifting. “The next generation of New Yorkers has been enlightened,” they see their role in a larger order that exist outside of their own financial gain. It is something she is seeing in her new home of San Francisco, “Young people here are very aware of how they’re changing the city.” The massive gentrification of the bay area is pricing many families not just out of their homes, but out of their lively hoods. “Once you get priced out, there’s nowhere for you to go,” she tells me. But efforts are being made to recognize this balance and try to support low-income housing and to invest in the community, rather than just take from it. It is a specific form of citizenship from a generation disconnected from politics, “I’ve struggled a lot with the idea of patriotism and being involved here...I often try to ignore the fact that I live here,” Asha tells me. The American political system, in her opinion, is completely outdated. “There’s so much division of choice,” she notes, “and not enough education for people to make those choices.” How many among us know what each of the local elected officials does? On ballots that can take up many pages, are any of us educated enough on every race? This problem has been addressed in some states like California with Mail-in ballots, “there’s no time pressure,” Asha notes. You can take your time to make a decision and look through the information in provided booklets on the positions and online. Far too many on the right push back on mail-in ballots and other efforts to increase voter participation, “maybe the thing that infuriates me the most are the voting laws. It’s inhumane,” she says. “Politicians are changing the rules as they go.”

“The whole system needs to be shaken up,” Asha says, “We don’t run campaigns that educate people on the causes.” The cult of personality surrounding candidates does everyone a disservice, in the long run, she believes. This goes both ways, both in support of individuals and vitriolic hatred towards them. “Hatred of a person in politics leads to the idea that it’s a religion.” Often this leads to politics being so heated that one fears to bring it up in polite company. This form of politics is foreign to Asha, “growing up in a liberal New York family, I wasn’t taught politics was a dirty topic,” she says, “I learned it is where all conversations should go.” Everything is political, and it should be treated as such. “Do I feel comfortable talking with Republicans about politics? Not really. But I don’t interact with many Republicans,” Asha tells me. “Liberals think we're accepting, were not!” she notes the ironic dichotomy that she and many others on the left find themselves in. How do preach inclusiveness but exclude the people you don’t agree with? I spend the rest of the afternoon walking through the Castro District of San Francisco, a gay mecca of sorts where much of gay history has unfolded. The bars and restaurants have provocative and playful names like Moby Dick and The Sausage Factory. The streets are gilded with markers of notable gay icons, pride flags and penis shaped souvenirs. I stop in the GLBT Historical Society museum on a small side street which is bookended by a gay club and a sex shop. “History might appear to be a dusty relic irrelevant to the present or a machine of the elite, manufacturing stories told only by the ‘winners.’ Yet, those left outside of traditional history have for centuries preserved and shared stories that have empowered and inspired younger generations,” the first plaque reads. The rest of the museum is a collection of object and relics from personal collections that tell a small part of a gay experience disregarded by history.

I pause for a long time in front of the case containing mementos from the life of Harvey Milk, the first openly gay man to be elected to office in the United States. He is a sort of mythic hero to me, a real organizer who worked to represent his community in the face of brutality. He knew in his heart that this was a dangerous venture, so much so that he recorded a political will shortly after his election. “If a bullet should enter my brain, let that bullet destroy every closet door in the country.” There is a large picture of Harvey in the museum with a button that when pushed plays the audio from that recording. As it begins to play, the picture of Harvey grows transparent to reveal a simple suit covered in spots of dry blood. It was the suit Harvey wore the day he was assassinated in the San Francisco city hall. It takes your breath away. To see the viciousness of prejudice in politics laid out in front of you is deeply moving. “I ask for the movement to continue, for the movement to grow, because last week I got a phone call from Altoona, Pennsylvania, and my election gave somebody else, one more person, hope. And after all, that's what this is all about. It's not about personal gain, not about ego, not about power — it's about giving those young people out there in the Altoona, Pennsylvania, hope. You gotta give them hope,” he says from beyond.

I continue down the block to the aptly named bar, Harvey. Colorized photos of the ‘Mayor of the Castro’ dot the walls, even one of him sitting in the bar that would later be renamed in his honor. I feel a special connection to Harvey as I sip my hard cider and talk with the regulars and bartenders. Is it possible to miss someone you never knew? His unrelenting insistence on the power of hope would be powerful right now. I miss him. The bar also brings to mind the other gay bar I stumbled upon early in my trip, back in Birmingham. Its dark and shameful windows, its fear feel like something frozen in a time much longer than a month ago. “I’m told it’s the first gay bar in America to have open windows,” the bartender says, motioning to the Twin Peaks up the street. I wonder if the people in Alabama have heard of such a place. I wonder if they can fathom me sitting in my Tejas pride shirt with the bar windows wide open letting the fresh air in with the sound of the drag queen playing music on the street corner. America is full of contradictions. “A lot of immigrants feel like they’re moving the goal post,” Brett tells me as we chat at Harvey’s bar. “These people have invested so much for their families and were changing the rules now.” This issue is particularly urgent in California that borders with Mexico and relies heavily on immigrant labor, it brings out strong emotions on both sides of the debate. “There are so many pissed off people. Most people don’t even want to have the conversation,” he notes. Brett is a consultant for healthcare companies and has watched as his work has grown increasingly political as healthcare continues to be a hotly contested issue. “You know, 70-80% of all healthcare comes from the government in some form…In California, Obamacare is robust,” he notes, “the whole conversation revolves around a very small market.” It is just one example of politics run amuck, in Brett’s opinion. “They are fighting for their lives as a party,” Brett knows about California Republicans, “they all live together and consolidate their vote.” That said, the way the districts are drawn in California (and everywhere for that matter,) “If you get elected, you’ll be there forever.” Many of these Republicans’ support for President Trump has not wavered despite the many scandals that have clouded his administration, Brett sees this as a reflection of the voters themselves. “So many people are so dissatisfied with their quality of life, you have to compromise your moral to make ends me. So when you see a politician do it, you understand.” This is not support purely in spite of immorality; it is support for immorality. There is an opportunity in a swindling politician to see the worst things you’ve done validated instead of stigmatized, that sort of support is hard to shake.

I wrap up my time in San Francisco and make the long trek through the valley towards Los Angeles, where it is unseasonably hot. Like really hot. Like I can feel it seeping the windows of the jeep even with AC on full blast-hot. Like I’m from Texas, and I feel hot-hot. I get settled in my cousin’s blissfully air-conditioned apartment, and we turn on Hannah Gadsby’s new Netflix stand up special, Nanette. This is the second time on this trip I have turned it on, and probably not the last as it is enthralling. One portion particularly stood out to me this time. In talking about how comedy does not provide a proper avenue to talk about sensitive topics, in this case, the story of her struggle to come out, she talks about the issue of discourse more broadly. Gadsby states: “I need to tell my story properly. Because I paid dearly for a lesson that nobody seemed to have wanted to learn. And this is bigger than homosexuality. This is about how we conduct debate in public about sensitive things. It's toxic, it's juvenile, it's destructive. We think it’s more important to be right than it is to appeal to the humanity of people we disagree with. Ignorance will always walk amongst us because we will never know all of the things. I need to tell my story properly because you learn from the part of the story you focus on.” For six weeks now, I have been searching for these words. The 100 pages of writing that have come before this post have been an attempt at scarping the surface of what she summed up in a stand-up special. We think it’s more important to be right than it is to appeal to the humanity of people we disagree with. Our problems are not a matter civility or partisanship—they’re about humanity. We have forgotten how to recognize one’s humanity. Abhorrent and reprehensible views come from people, real people. These views do not exist in some form of vacuum that consumes the humanity of the individual who holds them; we do that. We strip those people of their humanity because it is easier to understand, it makes us feel better. We learn from the part of the story we focus on.

Comments