A little less conversation

- Charlie Bonner

- Jul 6, 2018

- 8 min read

Fargo, North Dakota – Mount Rushmore – Salt Lake City, Utah Oh, beautiful for spacious skies, For amber waves of grain, For purple mountain majesties Above the fruited plain!

The isolation of the road is a welcome reprieve after the calamity of the Trump rally. I pull off on silly roadside attractions, grasping for some sense of normalcy on this road trip. Without sounding too dramatic, part of me feels today as if I am searching for the soul of something lost. Can the soul of a nation be found in the world’s largest buffalo sculpture? What about the enchanted highway? Maybe in the quiet moments of a milkshake at an old roadside stand? “Cowboys scrape shit from boots before entering,” the sign reads. I keep driving and searching until I arrive at my temporary home in Whitewood, South Dakota. The preceding days have made my feelings on this portion of the trip less than favorable. Something about being alone on a 200-acre ranch seems to lack the appeal it had when I booked the Airbnb a month ago. I have never felt such a longing to be in a city.

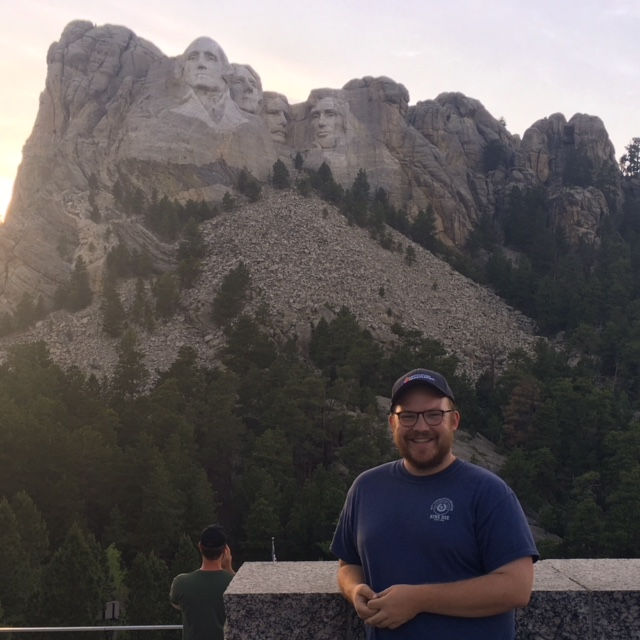

“I just bought this horse from the Indians; they don’t treat them right. I just couldn’t stand it,” my host tells me. We’ve just met, and she’s already delving into the ranch’s history, sparse amenities and throwing around anti-Native-American rhetoric like it is part of the property tour. Welcome to South Dakota. “We didn’t even know she was pregnant; we got two for one. I called and told em, and they said they would take the baby, I said no thanks. You can’t trust ‘em.” I drop off my things and get back in the car, a prison sentence after 10 hours of driving, but I need to make it before the sun goes down. I wait to get in behind RV’s and vans full of families from all over the country. I walk through an entryway of flags representing each state, the carved faces of Mount Rushmore peaking behind the waving flags as the sun sets behind their visages. It is something to behold. It is such an oddly specific form of patriotism, but one that does evoke some sense of pride. In this time when pride in country is statistically on the decline, it is funny to put into contrast this sort of spectacle. Years of painstaking physical labor and millions of dollars went into creating a ‘shrine to democracy.’ The winding path that leads to up to the busts features informational stops about the featured presidents and quotes from the artist, Gutzon Borglum. “This is the work that I love most, this intimate contact with the four men. As I become engrossed in the features and personality of each man, I feel myself growing in stature, just as they did when their characters grew and developed,” one reads. His admiration for these men was so intense that working on their likenesses enhanced his own self-worth—that’s some patriotism right there. On Lincoln, Borglum notes, “he was more deeply rooted in the home principles that are keeping us together than any man who was ever asked to make his heart-beat national.” This verbalization of service speaks to me. Isn’t that what service to the nation is all about? Giving of yourself to the greater good until your heart beats as one with the country. The more I drive, the more I speak to strangers all over the country; that is the thing I feel the most—a nearness to the nation. I stop and watch as families gather for photos with the Presidents in the background. I am too enamored to break the moment with my usual line of questioning. Instead, I stand and watch the memories be made, pictures that will end up in family photo albums or as cover photos on Facebook. Reluctant teenagers force smiles and toddlers pose like supermodels, large families squeeze close together to fit in the frame as some stranger struggles to figure out how their camera works. Maybe this is it.

Chasing the sunlight, I drive quickly around the mountain to make it to the Crazy Horse Memorial, a work in progress that rivals the busts of Mount Rushmore with a 563-foot carving of the Native American hero. It is far from finished even though work on the mountain began in 1948. The purpose behind it, as it was put to the sculpture “let the white man know the red man has great heroes, too.” A museum at the foot of the mountain features artifacts from all the great tribes of North America, models of the monument and a great gift shop. I park my jeep in the RV parking lot facing the mountain at the suggestion of one of the ticket takers. I climb on top as the evening's laser light show begins, a history of the tribes and the mountains brought to life on the hill where the memorial will one day be finished. The show concludes with a tribute to native veterans; God Bless the USA plays throughout the mountains—I can’t escape this song. I spend most of the next day at a local coffee shop with a sign that reads “guns are welcome on premises. Please keep all weapons holstered unless need arises in such case, judicious marksmanship is appreciated.” An elderly couple sips their coffee as come in, “where ya from?” they ask me, not knowing that they will receive a small diatribe about my trip. They smile with intrigue at my response, “should we invite him to sit with us?” the older man asks his wife as if I cannot hear five feet away. She agrees, and I join them, we talk politics, religion and a loose form of foreign policy for nearly an hour. “They kill Christians,” he tells me regarding Muslim majority nations, “they just go up to pregnant women, stab them in the stomach and watch the baby fall out. I don’t like to see that. They like to see that.” How we got on this subject, I will truly never know. He references Fox News as the source of such information about the Muslim World; he grows more animated the more he speaks of a land a million mile away. His wife chimes in from time to time, but mostly she drinks her coffee. “We read the Bible together every morning, she reads and verse and then I do,” he tells me, smiling at his wife of more than 50 years. It is how they stay grounded in this time of unrest, something they feel deeply in this small town. Their church has spoken of the plight of children separated from their families at the border; it bothers this couple, but not to the extent that illegal immigration does. His family came the right way, he tells me, immigrating from Sweden to evangelize in the states. “We better run to the post office,” he says, cleaning up their coffee mugs, cutting our conversation short.

I write for a while and then head to the next town over as this coffee shop closes. Parking spots are slim, so I pull in to a wine shop, hopeful that if I do a quick tasting, I can leave my car. The woman pours me a glass of sweet, sweet chardonnay as the heavens open, but sadly it is not a rainstorm as expected, its hail. She and I run to the window and watch as tennis ball sized ice blocks fall from the sky and pound into our cars. We are in the middle of what I can only imagine is the only tornado in South Dakota history, “I’ve lived here my whole life and never seen anything like this,” she tells me, her fear growing. Growing up in Texas, I am familiar with tornado procedures and find us a spot under the counter should this storm take a turn. Memories of my Oklahoman mother sitting on the front porch and watching the tornadoes roll are evoked, comforting the scared South Dakotan. She pours some more wine, and we wait. The wine is trash, but it is helping me cope with watching my car be wrecked in real time. After the clouds roll away, we assess the damage. Large, menacing, cracks cover the front windshield, and the hood is now cratered like the surface of the moon. Thankfully I can still see out the front to drive back to the ranch, where the other visitors were not so lucky.

A couple from Minnesota, Lindsey, and Dylan, describe driving through the mountains as the hail shattered their windows, “I’m still picking glass out of my hair,” Lindsey tells me. “sounds like we all need a drink,” I tell them, motioning towards the full bar at the center of the ranch. We pick through the dusty bottles and pull out an unopened and patriotically decorated bottle of Svedka, but no mixers can be found. The only one with a functioning car, I offer myself up as the errand boy, driving 5 miles down an access road to the closest Burger King to retrieve some sprite. If this seems like a low point, that’s because it is. We spend the rest of the evening sharing stories and talking about politics, sipping our backwoods cocktails as we go. “I blocked my mom’s number after the election,” Lindsey tells me. Her mom voted for Trump and the gloating splintered their relationship in the days following the unexpected win. “I just went to bed; I couldn’t watch it,” Dylan pipes in, the mood mellowing as we pause to remember where we were that fateful evening. It’s a ritual I’ve been through many times before. Like 9/11 or the Kennedy assassination, everyone has a story from that event. Where they were, who was with them, whether or not they cried, whether or not they saw it coming (they didn’t,) how close they were to the disaster zone (Pennsylvania.) That evening is not filed in our minds amongst elections. It is filed under national tragedies. We raise our glasses to our windshields, and we drink.

The next morning is long haul straight through Wyoming to Salt Lake City. The drive is 10 hours but covers what I believe may be the most beautiful corner of the country. The mountains rise and fall from the skyline with dramatic ease. I am captivated by the landscapes, by the protruding of the Devil’s Tower, by the pack of buffalo and the prairie dogs, by the clear blue skies. A great Texan, President Lyndon Johnson, once noted, "If future generations are to remember us with gratitude rather than contempt, we must leave them something more than the miracles of technology. We must leave them a glimpse of the world as it was in the beginning, not just after we got through with it." Something is reassuring about this glimpse into the past, something stabilizing about remembering what has come before and the political fights that went into preserving them (maybe I’m the only one that thinks about that part.) The drive is smooth, despite the light shining through the cracks in the glass like a prism. After 10 hours, I feel as though I know these cracks in the windshield like the creases in the palm of my hand. I have grown fond of them; they are battle scars for a well-traveled Jeep, proof that we saw incredible things and suffered accordingly.

Just west of my quick stopover in Salt Lake City are the Bonneville Salt Flats, on either side of the road white salt stretches for miles into the distant mountains. I stop for what I can only assume is the greatest photoshoot ever performed with a self-timer on an iPhone. As a group drives past, one screams out the window, “keep on living buddy.”

Comments