“There is no longer any room for hope.”

- Charlie Bonner

- Jun 5, 2018

- 6 min read

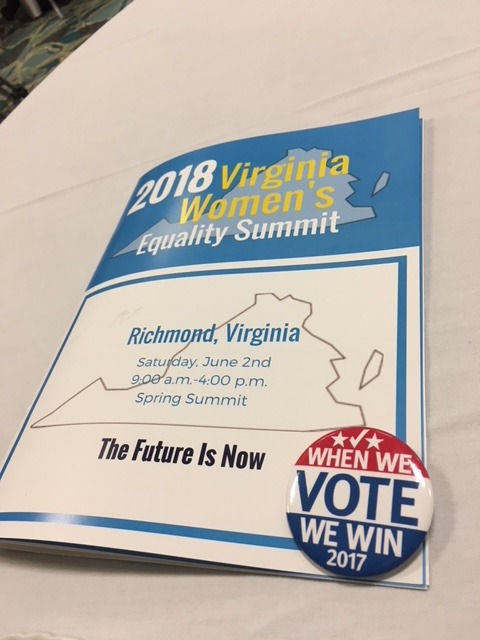

Richmond, Virginia “If people aren’t having children because kids are getting shot by the police—that is a reproductive justice issue,” one panelist noted. I am at the Virginia Women’s Equality Summit which is focusing on reproductive and economic justice as a pathway to empower Virginia women (Thank you Gina Baldwin for having me)

The mood is underlined with jubilation as 11 progressive women were elected across the state in 2017 that radically changed the agenda in the Virginia Legislature and allowing the governor to sign Medicaid expansion into law just one day prior, a long-term goal of Virginia Democrats. “Our patients don’t experience abortion as a right. I’ve never had a patient come in and say, ‘I’d like to practice my civil right to an abortion,’” a representative from Whole Woman’s Health expelled. Few people know better the effect the supreme court can have on this debate than Whole Women’s Health, who challenged the state of Texas on their restrictive anti-abortion laws. “It is important to engage in fights like that, even if you might not win,” she said. There was a fear in the progressive community that bringing a legal battle to the supreme court could actually limit reproductive rights with an unfavorable ruling. The lesson from this, she notes, “Don’t be afraid to do the right thing…[Justice] Kennedy was with us, what if he had been with us for the past ten years.” These legal challenges are fundamental to controversial political arenas in which the parties in power will not take action, “you have to challenge laws, and you have to sue people. You’re not going to get proactive legislation.” That said, this fight is not limited to the legal realm, it is a fight that individuals should take on in their everyday lives, “it starts with not being afraid to step into a conversation when you hear stigma…Don’t let that sit in the air,” one panelist noted. “We have to learn to step in even when it’s uncomfortable,” she said, “it takes a lot of courage to talk to someone face to face.” Every conversation can be an invitation to change hearts and minds.

Another panel discussed economic justice and the fight for a living wage, while breakout sessions sought to equip the activist in attendance with better storytelling skills and tools for lobbying. In a time when progressives are taking power in Virginia, activists are getting more involved to ensure that their issues are on the agenda, as one speaker noted, “I have to speak out, nobodies gonna protect me like I can protect myself.” Over at Union Market in Richmond’s Church Hill, I met with Liz Burneson, a recent law school grad from the University of Richmond and is an appointed member of Governor Northam’s Advisory Board on Service and Volunteerism. For all the confusion and disruption that 2016 caused, Liz, notes that the Virginia election on 2017 highlighted that “the people’s voice still matters.” Right now, though, our democracy is “so fucked up.” But there is a larger notion that this state of politics is bringing new people into the fold, as evidenced by the strong progressive wing growing in the Virginia Democratic party, “Virginia has been a good example, a wave of hope.” Things are different, “A lot of people won that didn’t have big donors, a lot of people won that didn’t have party support. A lot of people won because a lot of people are really fired up, and that was encouraging.” For too long, Liz notes, the party was afraid to be too bold for fear of alienating the other side, but the election of 2017, in her opinion, proved the opposite. “Medicare expansion is great, but what about single-payer,” she tells me, illustrating the notion that we can get the middle of the road policies accomplished while still pushing the agenda further. “My new thing from 2017 is dream bigger, don’t settle for what you think you can take because you might be wrong, and you might get way more than you ask for...you really don’t lose that much when you lose,” she tells me. It’s a result of the shortsightedness on behalf of state Democrats, “We don’t even know were winning right now.” Growing up in a more conservative family, Burneson is familiar with the importance of discourse; it’s one of the things that inspired her to start a group at U of R law to engage in non-partisan political discussions. The election of 2016 highlighted for her how little we speak to one another, an issue that is unusually pervasive in education, she added. The format of the discussions allowed each individual to express their point of view on a range of topics without the initial rebuttal of the others, hoping to prompt individual thought and understanding rather than just refutations. But it didn’t always work, “people can’t help but prepare their own rebuttal.” “I still don’t know where I stand on what it means to be able to talk to each other,” she noted, “I don’t know what else I can do…I don’t know; it just feels very personal now.” We then talked about that old version of politics that is often lauded as a better time, one in which you could grab a beer after a fierce policy debate, a notion that emphasized deals and compromise. “I wonder if for so long it was because it was all rich white dudes who could say ‘I don’t care what these poor people get, sure let’s trade on this.' It was easier for them to be partial because they were so far removed from it.”

An aside: this notion she brings up is really sitting with me as I write it out.The discourse of old was more pleasant, but who does that benefit exactly? Why is it that we think this system, one that completely lacked representation, worked so well. We want to give credence to this notion of getting down to the logic and ignoring the feelings lived experience, she notes, “it’s very gendered, and that’s how men communicate with each other very frequently. But also, for women or people of color or members of the LGBTQ community, their lived experience are a valuable tool. And it’s something they should be allowed to bring to the table…it gets to this platonic idea of just sitting down and putting your feelings aside, and that leaves out people’s experiences that count.” There should be room for personal experience and emotion in constructive and polite discourse, we agree. “I wonder if this idea that civil discourse is just supposed to be two people sitting at a table calmly and exchanging platitudes,” is actually asking us “why do you get so emotional?” This gap is becoming increasingly difficult to cross when many on the left feel as though those in power lack the empathy to understand why people are upset in the first place. “no matter what, how logically I explain my viewpoints, it doesn’t even matter if it’s going to go through his filter of ‘this is the way the world is.’”

Sunday afternoon, I continued my theme of historic places of worship and dragged my family to St. John’s Episcopal Church in downtown Richmond. In these pews, the second Virginia convention gathered in March 1775 to discuss the role of the colony in the rising conflict with Great Britain. In these pews, Patrick Henry would give his famed “give me liberty, or give me death” speech that defined the political uprising. An antique organ plays God Bless America as we are seated by men in colonial garb for the reenactment. “Liberty is the word this nation was founded on,” the presenter from the Patrick Henry Foundation begins before reenactors join tourists in the church’s aging pews.

I notice at this point how white the event is, and not just because the reenactors haven't pulled some Hamilton-esque color blind casting—everyone in the audience is white. Maybe it is just the stark contrast from attending the 16th street Baptist church last Sunday, but I grow uncomfortable with the demographics as the program continues. This is the most diverse part of Richmond, and not a single person of color is in attendance, while at many of the civil rights locations I visited, I was the only white person. It makes me wonder what we are all learning exactly. What versions of history are being told to different communities based on the color of their skin and the historical locations they frequent. This discomfort only grows as Patrick Henry proceeds to compare the plight of the colonies to slavery (I know it’s historically accurate but, damn.)

In character, he decrees, “there is no longer any room for hope.”

Comments